In the information technology (IT) world there are tools, solutions, and platforms to manage the multitude of information within an enterprise. There are systems for creating, storing, managing, and disseminating information – and of course all the plumbing in between.

As a result, nearly everything associated with information management falls under the purview of IT. But there is a subset of information management that is closely related (generated on computers) and so is treated like all the other data in this department. However, that subset, knowledge management, is nothing like its kin. And CIOs who are interested in helping business leaders meet organizational aims need to understand the differences.

A solid knowledge management system strategy requires important techniques and processes that have significant implications for the future of enterprises, IT, and software in general. In this piece, we look to make the management of knowledge more effective in achieving organizational aims by focusing on two facets: the coordination of data and making data more meaningful.

To understand the best tools and technologies necessary to for knowledge sharing requires understanding a distinction between the two.

Information Management vs. Knowledge Management

In IT, information management is the management of facts. It is the data that resides in CRMs, ERPs, log files, and IOT data. And often that data is tabular in nature – or structured.

The reality of present-day IT is that an enormous amount of data – both structured and unstructured – is produced and captured. Unfortunately, much of it is not in a form that is conducive to human use. That’s because the sheer amount of data, its fragmentation, and its storage in meaning-agnostic formats makes it difficult to find the signal in the noise.

But data without context is inert and requires overhead to continually apply and reapply meaning to it. Knowledge management is the contextualization of data. At each stage of capture, storage and recovery, effective knowledge management works to retain as much of the interrelation and setting of the data. Knowledge management is always occurring explicitly or otherwise, but effective knowledge management means proactively cultivating systems that care about making data meaningful and discoverable.

It is not a stretch to see knowledge management as the natural evolution in IT. Traditional IT is concerned with the mechanical aspects of information movement and storage. Knowledge management works to improve the effectiveness of this information by joining meaning with the data and considering how people will interact with it.

Many metrics can be measured to track the impact of improved knowledge management, but it’s tough to fully quantify the ripple effect of better codified knowledge across the enterprise; it has influence on every aspect of business activity. The future of IT is in large part concerned with moving higher up the ladder of meaning. Put another way, meaning is a major frontier in the ongoing expansion of what computers are able to address.

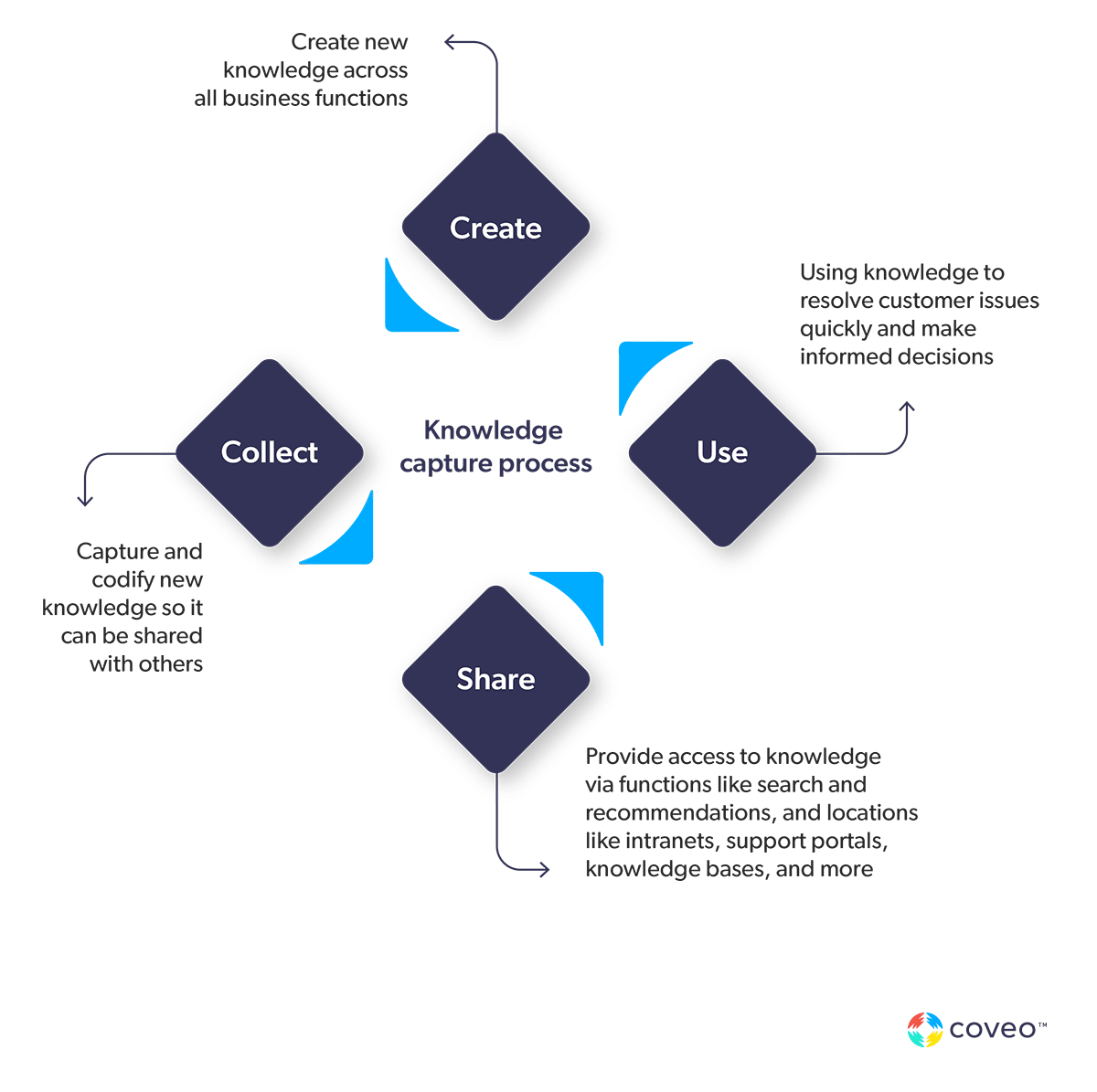

Knowledge is information with meaning applied. So how do you set up a system to manage knowledge transfer?

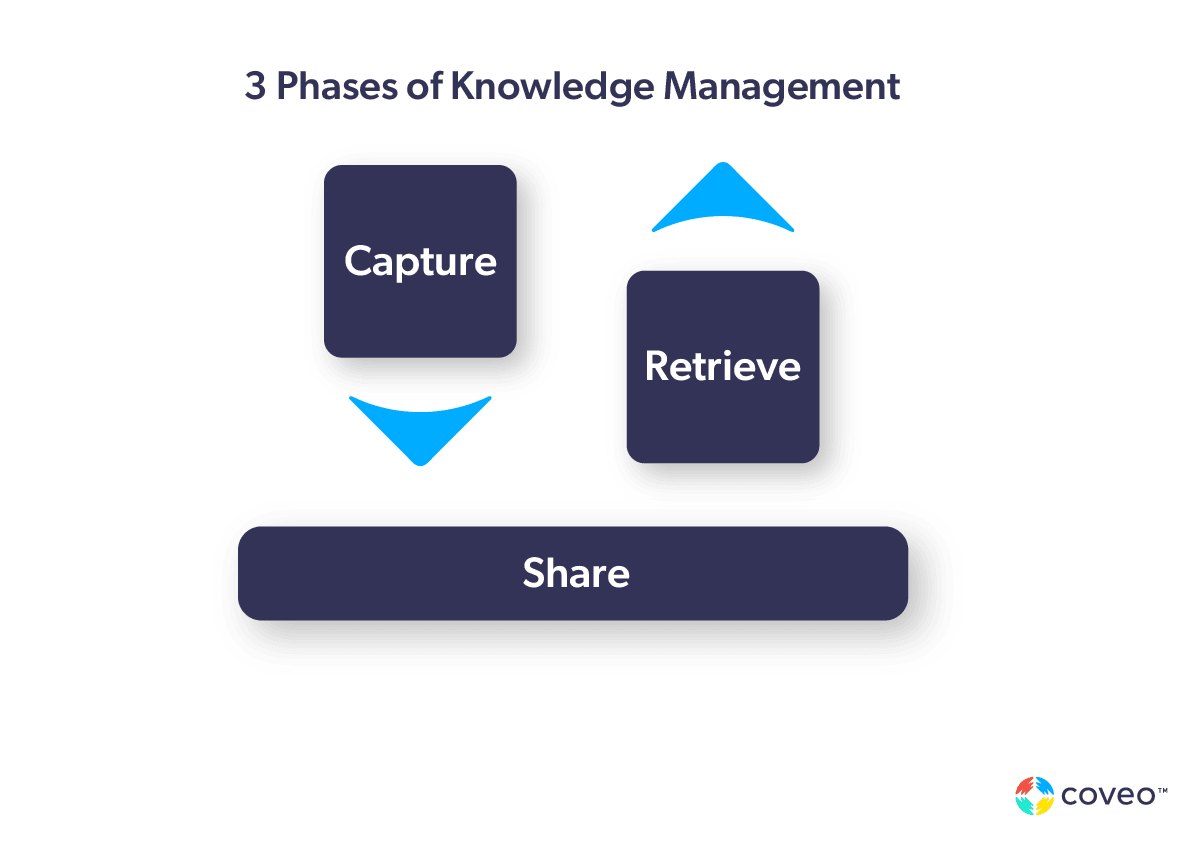

The Three Facets of Knowledge Management

Knowledge management implies an evolution of technologies and processes in how organizations capture, store, and retrieve information. These are the three phases or aspects of knowledge management.

Each of these has its counterparts in our software systems, which are input/output systems writ large. Current systems tend to have data widely scattered across heterogenous technologies, coming from diverse sources, accessed in a variety of ways. As an organization awakens to the urgency of knowledge flow, the first realization tends to be that the task appears monumental, in proportion to the scale of the business and its infrastructure.

Knowledge Transformation: Goals and Incremental Change

We could see a KM initiative as the leading edge of digital transformation and currently there is understandable transformation fatigue. It seems to be a never-ending, unavoidable task. The key is to tie knowledge management to business goals and move incrementally.

Every business is unique and the knowledge management ideal is dependent on their unique conditions. The pace and style of transformation is also guided by that enterprise’s characteristics.

It’s important to see an effective knowledge management strategy as an augmentation of existing approaches, rather than an upturning of them. The mental shift to considering how well information is flowing and how useful it is is the first step.

Specific Features of Knowledge Management

With the unique, changing conditions of each business in mind, consider an organizational knowledge ideal. The most prominent feature is the central storage of information in a form that makes it accessible to users when they need to modify or use it. A knowledge base is generally a single system which acts as concentrated storage. In particular, a knowledge graph or graph database are specific instances of a knowledge base that offer formalized modeling and linking of data, adding more powerful inference capability.

Enterprise search is another notable feature. It represents a key interface into the data – and content. Content being the unstructured information (e.g. emails, text, web, transcription) that helps in determining context.

Enterprise search works to make data more meaningful and accessible to users by incorporating their context and intent. Enterprise search can help bridge the gap when information is diversely held across data stores like cloud apps, network drives, shared documents, version control, wikis, and databases. It does so by unifying and indexing information to present a consistent, KM system-like façade that user interfaces can address.

Semantics

A key distinguishing factor of knowledge is the role of meaning. Knowledge is active. It has significance and drives action. When an employee or customer is looking for something, an effective knowledge management tool employs semantics – the study of meaning – to divine what their purpose is and guide them more effectively to the right place.

This means less duplicated effort, less wasted time and frustration and generally better communication across the enterprise. The overall effect is less churning activity and more high-impact, high-leverage action that is the result of clear organizational reasoning.

Human beings are masters of semantics. From birth they naturally grasp and move toward greater degrees of understanding in meaning and context. Machines are helpless. They must be painstakingly instructed to incorporate – to imitate convincingly, perhaps – an innate characteristic of human consciousness: why something is important and to what it relates, rather than just that it is.

A person might say “the cat is hot.” That probably means a furry animal is warm, but it might mean Charlie Parker was on fire that night. Context matters.

The most obvious place where semantics are introduced into software systems is as semantic search. Enterprise search generally works to incorporate semantic search.

However, pure semantic search can fall short.

Usage data shows that the highest volume queries in most basic query-based search scenarios are less than three words — not enough to truly give relevant results. Coveo takes a more systematic approach to search algorithms. By combining semantic signals with other lexical and behavioral signals, it is possible to reduce ambiguity and understand the user’s intention in any situation.

Knowledge Management in Perspective

Arguably the most daring, visionary leap in the history of computer science was Alan Turing’s paper On Computable Numbers. It described in conceptual terms what became our digital computers, staking out the mental territory in advance. It’s no accident that the same person who described this space, what we now call the Turing Machine, also described what we now call the Turing Test: the attempt to define if and when a computer could be considered as having intelligence.

This gulf between people and their digital technology is a central source of friction at all levels. It is especially detrimental to enterprises, serving as a divide between the organization and its employees and customers. By understanding what Turing was wrestling with and understanding its historical context, we can put the efforts of modern business to improve the meaning of information as the latest in an ongoing tale.

Charles Babbage was already thinking about this in the 19th century when he wrote, “we may propose to execute, by means of machinery, the mechanical branch of these labours, reserving for pure intellect that which depends on the reasoning faculties.” He was foreshadowing both Turing and the general effort to determine where the boundary of mechanical and human reasoning may be placed, and to what extent they may be brought together.

This also leads towards complexity theory as hinted at by Godel’s letter to Von Neuman and explicitly codified in Cook’s famous complexity paper, an outcome of which is the still-standing NP vs P problem. In short, what class of problems are reducible by clever algorithms to time/space viable solutions. We may then ask regarding knowledge management to what extent the semantic meaning of data is so reducible.

Role of AI/ML

Modern computing attacks this problem in a direct and practical way in the fields of artificial intelligence and machine learning. In good coder style, AI/ML goes at the problem of making software more intelligent by building it and seeing how well it can be made to work.

The general drift of things is that without fighting the philosophical battle, an immense amount may be gained by improving human-machine interaction by virtue of pragmatic knowledge management techniques.

We can be focused on something very practical like delivering a better customer service experience while we are working to make systems more human-amenable. The bottom line is that we need to make our software systems more proficient at interacting with humans. To ignore this aspect of technology is to court disaster by missing a vital current that influences the very essence of computing.

Internal and External knowledge

Knowledge management is sometimes understood to mean the inner facing flow of information in an organization. That’s something of an arbitrary distinction. More useful is to consider information as having two facets, the internal and external. Some data is intended for an internal audience, some for external.

More granularly, information access is determined by permissions, well defined or otherwise. Therefore, we can say that security is a central characteristic of knowledge management.

Employee access is a focus of managing knowledge, largely because customer experience has taken center stage for so long. Awakening to the importance of employee data usefulness and its impact on overall business performance is then another realization inherent in unlocking existing knowledge.

Knowledge Graphing and 360-Degree Knowledge

A huge amount of progress is possible here for the reason that knowledge management is a frontier just now being explored in real-world application. Effort to incorporate meaning can yield asymmetrically large benefits in many cases. Adding semantic search to employee portals, for example, can radically improve their capacity and their contentment as well.

More thoroughgoing change is also in the cards with how information is stored in knowledge graphs and in how it is envisioned in organizations and societies under the banner of 360 degree knowledge.

Knowledge graphs and graph databases are a fairly significant architectural change to enterprise, but the mental shift represented by 360 degree knowledge is an even more profound change. It evolves the people, processes, and structures that underpin the daily operation of organizations.

Keep Knowledge Flowing

The present day reality of information technology is that an enormous amount of data – both structured and unstructured – is being produced and captured. If it is still balkanized, then you have effectively cut off knowledge sharing — the essence of knowledge management.

Knowledge interacts, overlaps, and modifies itself within the system that enables it.

Bringing data together from manifold flows is the first, practical task of managing knowledge resources. Only then are we able to address the deeper concern: bringing information nearer to the realm of human understanding.

Coveo Software is a trusted partner that delivers many aspects of knowledge management like semantic search and knowledge graphing. Learn how Coveo Platform™ helps business in the quest for effective knowledge management initiative.